Metrology, Process & Quality Control

Laser metrology uses principles of laser interferometry, holography and diffraction to measure area, distance, vibration and surface properties like flatness and roughness. The use of lasers allows for precise, non-contact methods to ensure quality control and compliance in many industries like automotive, medical and aerospace.

They can detect process nonconformances or safety concerns such as gas flow leaks on a pipeline, scratches and digs on a medical device lens or dimensions out of tolerance on a car engine. The unique intersection of lasers being both non-contact and able to “visualize” defects out of the visible spectrum means better detection with lower risk of contact damage and higher productivity.

Assuring these laser beams are properly aligned, focused and sized are important for optimal performance. For best performance, regular laser beam profiling is recommended. Information on beam parameters listed below.

Metrology, Process & Quality Control – Laser Use Examples

Categorized by Electromagnetic Spectrum Region

UV | ✓ Interferometry ✓ Assorted metrology |

Visible | ✓ Alignment, Holography ✓ Holography with HeNe (~1 - 20 mW) ✓ Optical Interferometry for measuring optical defects |

Near Infrared (NIR) & Infrared (IR) | ✓ Distance Measurement, Gas Sensing including Pollution Monitoring, LIDAR, Spectroscopy ✓ LIDAR with fiber pulsed (~10 - 200 W peak) ✓ Spectroscopy with QCL pulse (~0.1 - 5 W avg) |

Metrology, Process & Quality Control – Important Beam Parameters

Intensity

Irradiance Fluence Continuous & Pulsed |

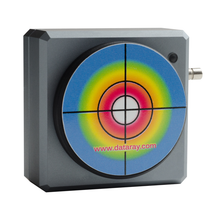

Adequate beam intensity distribution means sufficient energy transfer to the target surface. Measurement accuracy, precision, reliability, safety and process conformance require the proper application of beam intensity (or fluence). Regular beam profiling can help maintain metrology laser beams to specification. The 2D beam profile to the left shows a Gaussian beam intensity profile where the intensity is greatest at the center, white, and decreases moving outward toward the outer circumference, blue. Profiles like this give relative information about the intensity distribution. For other beam shape profiles used in metrology, see beam shape, below. The power applied at the beam waist divided by the spot size also gives information about the power intensity (for continuous beams). Metrology laser power ranges ~mW - several kW.

Note — For a continuous beam, the terms intensity, irradiance or power density are used: power divided by area, W/cm². For a pulsed beam, the term fluence or energy density is used: energy divided by area, J/cm². A pulse, repeated at the pulse frequency, will have peak irradiance and maximum pulse energy values reached during the pulse. |

Beam Waist Spot Size Focus |

At the focus, the beam diameter reaches a minimum, often referred to as the spot size or beam waist diameter. Focusing a beam to a smaller spot size will increase the density in that spot and vice versa. It is important to apply the optimal amount of power or energy at the specified spot size. Too large or too small will affect the target location and may lead to some of the defects mentioned previously. Some common spot size values in metrology, process, and quality control vary from microns to several mm. |

Focal Plane Focal Distance |

The focal plane of a non-collimated laser beam is generally where the beam is focused to its smallest spot size. The focal distance is the distance from the focusing lens along the axis of propagation to the focal plane and can vary depending on the presence of other optics: the laser source, focusing optics and possible beam shaping devices. The focal plane, in many cases, lines up exactly with the material surface or working plane, but may be offset; for example:

|

Beam Shape

|

Common shapes:

Beam profilers provide a quick and effective means to quantify the relative intensity distribution of a beam to verify beam shape. |

Beam Propagation |

Beam propagation is the behavior of a laser beam propagating through free space and is described by M² (beam quality), divergence and pointing. M² characterizes how close a power intensity profile is to a “Gaussian” beam and can give a sense of how focused the beam is.

Divergence describes the angle the beam diverges outward from the beam waist into the far field, much beyond the Rayleigh length. In contrast, divergence near zero is a way to confirm a beam is collimated, for example before being focused. This helps to ensure that once the beam is focused, it will be at the correct spot size and location. Pointing is the angle of laser beam propagation with respect to the optical axis. A pointing value of zero means it is perfectly aligned with the optical axis. It characterizes how much a laser stays on center as it gets farther from the laser source, including accuracy and precision. Pointing measurements support better beam alignment. Misalignment may compromise measurement accuracy and precision. Misalignment can be caused by thermal fluctuations in the environment or in the laser system of high power lasers, as well as due to attenuation and time. |

Have questions or need help identifying the right solution for your application?